The next few weeks are going to be very busy for me - not only do I have Zenkaikon coming up next week, but in April I'll be on a family trip out of the country. (No marker hunting? What do normal people do on vacation?) Throw in the job, the writing gigs, the book I'm trying to finish... well, there's a reason I'm actually working on this blog post the night before it goes live instead of on Wednesday morning.

I'm not complaining, though. I do like to keep busy. Now if it would just stop snowing...

For today we're going back to that very un-snowy day last August, when my mother treated the BFF and me to a day in Philadelphia and helped me catch some markers there. This was one of the markers I spotted while we were riding on the upper level of a double-decker bus tour; for that reason, my current photo of the marker is not the clearest, and I promise to replace it with a better one at the first opportunity.

|

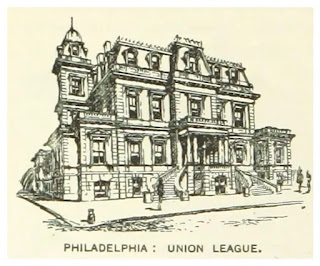

| The marker stands in front of the Union League's headquarters at 140 South Broad Street |

To start, we need to know what the Union League was (and is). These were kinda-sorta secret clubs for society gentlemen. The first one was started in June 1862 in Illinois; the second, which is the subject of today's quest, was established on November 22, 1862. Other Union Leagues soon followed, each one formed individually but in harmony with one another. Their purpose was to encourage and promote loyalty to the Union and its army, and particularly to support the policies of that tall guy with the beard who had just been elected President of the United States. This is reflected in their Latin motto, Amor Patriae Ducit - "love of country leads." They were originally non-partisan, at least on paper; but by 1864 they were openly allied to the Republicans and turned out in force to get Lincoln re-elected, although they also threw their support behind Democratic candidates who were in favor of the Union.

The largest of the clubs, which were those of Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, counted among their members the wealthiest and most prosperous pro-Union gentlemen of local society. They worked to raise funds for service groups that provided aid to the Union soldiers; this included the Sanitary Commission, so my longtime readers can probably guess that they were part of the force behind the success of the Commission's Great Central Fair of Philadelphia. Meanwhile, other less elite chapters continued to spring up, admitting working class men to their ranks, as well as Ladies Union Leagues. The northern states were, for a time, practically dotted with these, and in 1863 they all became united under the banner of the Union League of America, with a central headquarters in Washington, D.C.

After the war ended, Union Leagues began to also appear across the southern states. Part of their mission was to help the recently freed male slaves register to vote (and encourage them to vote Republican when they did), as well as to educate their new brethren on political issues and promote civic projects. Out of necessity, the southern Union Leagues were considerably more secretive than their northern counterparts. This was because of the Ku Klux Klan, who despised the Union League and its efforts to assist black voters; they were known to sometimes assassinate Union League leaders, as well as doing their best to scare black voters away from the polls, and so for the safety of the League members they had to hide their work as much as possible.

During the Restoration period, the Philadelphia chapter turned its attention to other philanthropic endeavors, though always with a view of supporting American military. This carried into the 20th century and its various wars. The membership of the club remained male and white until the 1970s, when black men began to be admitted, and then in the 1980s, they changed policies again to allow women to join. By this time most of the other chapters of the Union League had dissolved; today, only Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago still have Union Leagues to their name, making the Philadelphia chapter the oldest surviving Union League in the nation.

The Union League of Philadelphia continues to adhere to the spirit of its founders through charitable works and fundraising. In 2019, they streamlined their civic projects into a single entity called the Legacy Foundation, which maintains the League House, cares for its historic collections, and performs various kinds of outreach in the community. This includes lectures on a variety of topics, educational programs for high school students, scholarship programs for secondary education, and the Good Citizenship Award, among other things. The Heritage Center, which houses the League's collection of Civil War memorabilia and other historic artifacts, is open to the public on alternate Tuesdays and Thursdays from 3 to 6 p.m., and on the second Saturday of each month from 1 to 4 p.m.

I couldn't help but wonder, how does one become a member of the Union League of Philadelphia today? Well, you first have to know someone who's already a member, who can put your name up for consideration. You'll then attend a reception for potential members, after which you request and complete a proposal. The exact nature of this document is not known to the public, because I guess even after 160+ years they like to still be a little bit secretive. It's part of the fun. The next step is to find six sponsors who are willing to write letters of recommendation for you, then send those letters back with your proposal. If you're invited to an interview and you prove to be sufficiently impressive, you'll be invited to join. The initiation fee is a mere $7,500, and then after that you'll have to pay annual dues; the exact figure varies a little depending on certain criteria, but a standard membership is usually around $6,200 per year. (These were the figures as of last autumn, according to an article I have linked in my sources.)

Unfortunately, the blog isn't quite lucrative enough to let me join the Union League anytime soon. But it certainly was interesting to learn about their history.

Sources and Further Reading:

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I would love to hear from you!