As you're reading this, I've just returned from my first-ever visit to Lititz, in Lancaster County. Spent some time collecting markers and learning about pretzels, so you'll see some of the pictures from the trip in coming months.

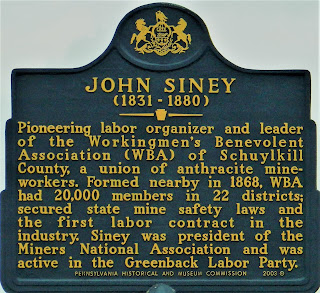

For this week's quest, though, we're heading into the coal country. Mining coal in Pennsylvania remains a big part of our history, as we've already had occasion to note in this blog, and this gentleman's story is a significant thread in the tapestry.

|

| The marker is on PA Route 67 (Claude Lord Boulevard) less than half a mile north of West Russell Street, St. Clair. |

While living in Wigan, John helped to organize the Brickmakers' Assocation of Wigan, for which he served as president seven times. In 1863 he set sail for the United States, settling in the anthracite mining town of St. Clair in Schuylkill County; other immigrants from Wigan had settled in the same area, so he knew some of his neighbors right away. It was probably not the best time to be coming to America, what with that Civil War we had going on, but he found work first as a laborer and then as a miner. Mining was an industry that always needed more workers, and one of the few industries willing to hire immigrants, so getting a job wasn't hard. What was hard was getting a decent wage, and John joined his first strike in 1864, protesting for a pay raise.

The strike was successful - the mine bosses reluctantly raised the wages - but it came at a cost. Coal was a vital commodity for the Union in the ongoing war, and the strike threatened its supply, so public sentiment was not altogether in favor of the strikers. Worse, the success of the strike was short-lived; the war ended in 1865. Coal was necessary during the war because it powered naval ships and railroad engines, both of which were needed to transport soldiers and munitions, but with the cease-fire came a reduced need for either of those things. It was still an important resource, as coal had replaced wood as the primary means of providing homes with heat and light, but the demand during peacetime was not as great as it had been during wartime.

With sales of coal dropping, the mine owners slashed wages by as much as 35%. This was more or less understandable, and the miners didn't protest too heavily... at first. In 1868 there came a second wage cut, and this time the miners were less inclined to accept the situation. A six-week strike was the response, during which John Siney proved himself to be a natural leader, taking on tasks like renting a building to serve as the strike's headquarters and establishing a fund to support miners' families until the situation stabilized. He also helped to organize a St. Clair chapter of the Workingmen's Benevolent Association (later renamed the Miners' and Laborers' Benevolent Association), which would provide the workers' families with sick pay, death benefits, and financial support during additional strikes.

To say he was successful would be an understatement. The WBA, as it was called for short, was the driving force behind legislation passed in Pennsylvania which determined that the legal work day would be eight hours long, provided there was "no contract or agreement to the contrary." As a result, the WBA became a county-wide organization, representing more than 20,000 miners, and John was elected chairman of the executive board, which provided him with a salary. This was very important; John had a young daughter, Margaret, whom he was raising alone (her mother Mary is believed to have died in childbirth back in England), so this arrangement meant that he was able to devote himself full-time to his union work while still providing for Margaret as she grew up.

The influence of the WBA began to spread beyond Schuylkill County's borders in 1869 when, in September, the Avondale Disaster struck Luzerne County. This has a marker all its own and will be quite a sad post, but to summarize, a fire broke out in a coal breaker in the Avondale mine. 110 workers were killed in the shaft beneath the breaker, suffocated by the smoke because the mine was poorly ventilated and had no secondary exit. John traveled to Avondale and urged the other miners to join him in his efforts to fight for their rights. "You can do nothing to win these dead back to life," he said, "but you can help me to win fair treatment and justice for living men who risk life and health in their daily toil." Many of those listening would join the fight, and the WBA continued to press for mine safety laws to prevent disasters like Avondale from happening again. Laws passed in Schuylkill County required all coal mines to have more than one way for the miners to escape, and stated that ensuring proper ventilation was the responsibility of the mine owners; however, even with state mine inspectors touring the sites, these laws were difficult to uphold because of the power and influence the mine owners wielded.

John began to involve himself in labor politics. In 1873 he helped to launch a national union called the Miners' National Association, which was dedicated to improving safety in the mines, resolving disputes through arbitration rather than strikes whenever possible, and reducing labor hours. The MNA also, like the WBA before it, agreed to provide benefits for striking workers when the need arose. Remember that for a bit later.

More strikes continued to happen throughout the coal region as the WBA did its thing. In Clearfield County, a marker recalls the strikes of 1869, 1872, and 1875, including the shooting of four men at a railroad station in 1872. Not helping matters was the 1873 agreement between railroad and coal barons, which resulted in the first recorded price fixing in U.S. history, and the wage cut which followed. Another strike, another wage cut. John himself was arrested for riot and conspiracy following the 1875 strike, and his trial was one of those which caught the attention of the entire country. Meanwhile, some important figures (like Franklin Gowen of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad) became more and more convinced that a secret organization of miners called the Molly Maguires was behind much of the conflict. I've talked about the sad fate of some of those men already.

The 1875 strike was the worst of all, known as the Long Strike. It lasted for six months and was a consequence of the Panic of 1873, a financial crisis triggered by the collapse of a few banking houses; this crisis had a negative impact on the coal industry and led mine owners to start reducing wages again. John warned the WBA members to take the matter very slowly and carefully, because under the difficult circumstances, he didn't think strikes would work this time. He was right, but they didn't listen to him, and as a result the MNA had to pay out much more in strike benefits than its treasury could realistically afford. Faced with economic ruin, the MNA folded after the Long Strike. The WBA was also shut down a few years later; most of those convicted of being Molly Maguires and sentenced to hang were members of the WBA, and the organization couldn't survive the bad publicity. It's surmised by modern historians that destroying the WBA was the real goal of the investigation into the Mollies.

With the MNA gone and the WBA in the process of folding, John basically gave up on union work. He went back to Schuylkill County and bought a tavern. His daughter was grown, and he finally remarried in 1876; with his second wife, Margaret Behan, he had a son, John Jr., who later worked for the IRS. The years of difficulty took their toll on his reputation, with some of the miners blaming him for being too conservative in the face of the Long Strike.

The years of working in the coal mines also took their unfortunate toll, and like so many of his colleagues, John succumbed to "miners' consumption." With coal dust lining his lungs, he died in April 1880 at the age of just 49. His funeral was attended by more than 1,500 people, and the cortege of mourners traveling from church to cemetery was more than a mile long. His death notice and obituary appeared in multiple newspapers, but strangely, some claimed that he had no children; others stated that he had a grown daughter but were unaware of his son's existence.

John's work may not have been entirely successful in his own lifetime. However, it paved the way for later efforts by the United Mineworkers of America. Their leader, John Mitchell, made a point of honoring John Siney's contributions to the struggle, and even made a special pilgrimage to pay his respects at the St. Clair cemetery where the earlier champion of workers' rights is at rest.

Sources and Further Reading:

Wynn, Jake. "A Tribute to a Coal Region Labor Leader - John Siney." Wynning History, February 22, 2019.

Simkin, John. "John Siney." Spartacus Educational, September 1997 (updated January 2020).

John Siney at the Samuel Gompers Papers Project

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for this. I have advertised this on my blog. This is a great intro to labor history. I think that one of the untold stories is that so many WBA, NMA and Mollies members went west and built the labor movement there. It's significant that the first lodge of the Ancient Order of Hibernians was in the Pennsylvania anthracite fields and the second was in Colorado. Again, many thanks!

ReplyDeleteThank *you*, Bob! I appreciate the shout-out and will let my followers know about your blog too!

DeleteDoing genealogy research I noticed on an obituary of my great grandmother sister that a poll bearer was John Siney from st. Clair. The date is 1915 so this must have been his son.

ReplyDelete