This is a new one for the blog - the first cross-county post. Throughout Pennsylvania there are a number of markers which are related - either they contain the same information in two different locations (which is the case today), or they're a series of markers which, when put together, more or less tell a story. It's not going to be easy for me to do some of these; for example, there are several markers related to the various canals that will take me a long time to collect. But this one, which has just two, I can do.

Odd as it probably sounds, given the subject matter, I've been looking forward to writing this post. It contains one of the most interesting and obscure pieces of local apocrypha that we have in the Lehigh Valley region. I only waited as long as I did to do this one because I needed a couple of photos from the other location in the story. Now that I have those, here's how we'll finish out the summer - with the deaths of ten men.

Odd as it probably sounds, given the subject matter, I've been looking forward to writing this post. It contains one of the most interesting and obscure pieces of local apocrypha that we have in the Lehigh Valley region. I only waited as long as I did to do this one because I needed a couple of photos from the other location in the story. Now that I have those, here's how we'll finish out the summer - with the deaths of ten men.

|

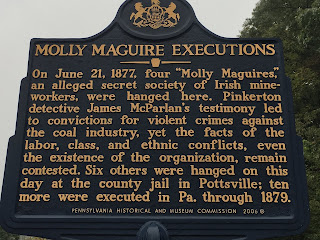

| Top: Marker situated outside the Schuylkill County Jail, Pottsville; image courtesy of Liza Bazarian. Bottom: Marker situated outside the Old Jail Museum, Jim Thorpe, Carbon County. |

You might recall that when I wrote about the Carbon County marker, I spoke of the Old Jail Museum, which is possibly the most curious of the landmark attractions in historic Jim Thorpe. It wasn't always a museum, of course; it really was the Carbon County Jail for more than a century, until it was replaced by the more modern Carbon County Prison. Inmates were housed in the old jail until January 1995. It was completed in 1871 and is considered an excellent example of 19th century prison architecture.

So is the Schuylkill County Prison in Pottsville, which dates from approximately the same time period. Unlike the Old Jail Museum, it's still a functioning prison, meaning that you can't tour it and you're not exactly encouraged to take photographs either. Both structures have a similar aesthetic, bearing resemblance to small ancient castles overlooking their provinces, though the SCP has a round tower while the Old Jail Museum is more square and angular. But the thing they have in common is the Molly Maguires.

(There is a song called "Make Way for the Molly Maguires" and every time I start thinking about this subject, I get it stuck in my head. Here, enjoy the earworm.)

To give a little backdrop to the Molly Maguires, Ireland in the late 1800s was not like the idyllic scenes I visited a few months ago during my trip to Europe. I'm sure if it had been, no one would have ever left. Instead, there were severe economic hardships, caused in part by the famous potato famine, and many people had to either leave the country or risk starving to death. The promise of the United States, with those streets paved with gold and other legends, lured many of them here. Pennsylvania's coal country was a popular place for them to settle because coal mining was one of the few industries which not only always needed more labor, but was willing to hire Irish immigrants. You may have seen one of the signs from the time period which reads "Help Wanted - No Irish Need Apply." (A friend of this blog, John, grew up in the area and had one of those signs in his bookstore until it closed. He, of course, is Irish.)

|

| Top: The Old Jail Museum in Jim Thorpe. (Note the ad for ghost tours, available in October.) Bottom: The Schuylkill County Prison in Pottsville; image courtesy of Liza Bazarian. |

Working for the coal companies was frequently not the dream job they might have hoped. Once a man signed on with a coal mine, he essentially belonged to the coal mine - he lived in a house owned by the company, and had to make all of his purchases from the company store. The company would either deduct the cost of his purchases from his pay, or else pay him in scrip, which was a sort of special currency that wasn't good anywhere except at the company store, and if he tried to go anywhere else to buy what he needed he was likely to be fired. Since being fired also meant being evicted, the miners were pretty much kept men; and since the company owned the store, they could set whatever prices they liked. As the Old Jail Museum's owner Betty McBride points out in one of her writings, it wasn't unusual for a miner to owe the company money by the end of the work week rather than be able to expect a paycheck.

The 1873 agreement between a group of railroad and coal barons led to the first recorded price fixing in United States history, setting the price of coal at $5 a ton. This directly led to worsening conditions for the mine workers, whose wages were cut. A strike was unsuccessful and followed by another wage cut. There were violent brawls and other crimes committed, and the blame was placed on a secret organization of Irish miners known as the Molly Maguires.

(As I mentioned in the Carbon County post, this was all illustrated in the 1970 film The Molly Maguires, based on Arthur Lewis's book of the same name. Richard Harris played James McParlan, the spy from the Pinkerton detective agency, and Sean Connery played John "Black Jack" Kehoe, one of the Pottsville miners who was hanged in 1878. Parts of the movie were filmed in the Old Jail Museum, as well as in the Carbon County courthouse and nearby Eckley Miners' Village. Despite the excellent subject matter and cast, however, it was a box office bomb.)

Exactly who the Mollies were is unknown, although the name is believed to have been that of a woman in Ireland who aided a similar secret society. Many historians today believe that no such group ever even existed, or at least not in Pennsylvania, and that it was merely a plot to create a scapegoat for the troubles so that the public would be suspicious of the miners. The plot is believed to originate with Franklin Gowen, president of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Company and the Philadelphia & Reading Coal and Iron Company, who was the one to periodically send information to the press about the criminal activities of the so-called Mollies. He was also the one who hired the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to investigate the miners and root out the spies. One of the detectives, James McParlan, took the name James McKenna and worked in the mines alongside the suspected miners in order to earn their trust. He gave Gowen a vast deal of information which was used to arrest several of the alleged Molly Maguires, who were then imprisoned in the two jails.

|

| The main cell block of the Old Jail Museum; the reconstructed gallows stands at the far end |

The first executions, the ones commemorated on the markers, took place on June 21, 1877. Four men - Alexander Campbell, Michael Doyle, Edward Kelly, and John Donohue - all met their end on a scaffold inside the Carbon County Jail, which was specially constructed to hang them all at the same time. In Pottsville, six more - James Carroll, James Roarity, Hugh McGehan, Thomas Munley, Thomas Duffy, and James Boyle - were hanged two at a time on the prison lawn. Each had been convicted of murdering someone affiliated with the mine where they worked; most protested their innocence to the end. Some still had living parents, and some were married, and some had children. Edward Kelly, an alleged Molly who was hanged later, was just 18 years old; James McDonnell, one of the last to be hanged, was 41. In other words, they were people. Many of them were good people, and at least a few of them - possibly all of them - were entirely innocent. Of course, eventually labor laws were put into place that would make life more bearable for miners and other laborers, but much too late for these men.

|

| Up close and personal with the gallows |

Then there is that bit of local apocrypha I mentioned. You see, in the Old Jail Museum, many of the former cells are unlocked or have had their doors removed, and during a tour visitors may go inside. This is also true down in the basement, where solitary confinement took place in the pitch black. However, cell #17 is sealed. Visitors can only look through the window on the door. This is because cell #17 is home to the infamous handprint, left by one of the Mollies before his execution. It was thought for years to be that of Alexander Campbell, although research has shown it may have been Thomas Fisher's. Whichever the case, the story says that the prisoner rubbed his hand on the cell's dirt floor and then smacked the wall to leave the print, declaring that he was an innocent man and the handprint would stay forever as proof of that. He was, of course, then hanged.

But more than a century later, the handprint endures. In an effort to get rid of it, various wardens over the years have scrubbed the wall, repainted the wall, and even cut out and removed the section of the wall where the handprint sits. It always comes back. Finally, in 1975, the warden hired a team of scientists to examine the wall and determine what was there... and they found only paint. There is no clear reason why this handprint is still there. Maybe it really is a testimony to its owner's innocence. It's been featured on Mysteries at the Museum (season 11, episode 11) and has been examined by various ghost hunters and paranormal experts.

And yes, I've seen it with my own eyes. It made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. I do not have a photo to share - it's forbidden to take pictures of the print, and although I know a lot of people ignore this rule, I'm not one of them. Visitors can buy a postcard of the handprint in the gift shop.

The Old Jail Museum today is in the hands of Thomas and Betty Lou McBride, a pair of locals who are proud to share its history. The building is open for tours Memorial Day through October. Times, admission fees, group tour information, and parking information can be found on their Facebook page (below) or by calling 570-325-5259. Ghost tours are available during the month of October, though that's also the month of Jim Thorpe's annual Fall Foliage Festival so prepare for heavy traffic going into town. I've done both the regular tour and the ghost tour, and they're both incredible. It probably isn't the legacy that the Molly Maguires ever expected to leave, but at least by letting the public visit the jail and hear their stories, the McBrides are keeping their names from being lost to time.

Since I couldn't show you the handprint, I'm going to instead close this out by sharing a photo I took during the ghost tour in October 2018; this is down in one of the solitary confinement cells in the basement. When I took the picture, everything seemed normal... but have a look just to the right of the shackle on the wall. See the two pinpricks of light? Yeah, I don't know what they are either, but I'm one of many people over the years who has caught a picture of something strange in that building. I guess you just have to see it to believe it.

|

| Click for a larger version of the image |

Sources and Further Reading:

Official website of the Old Jail Museum

The Old Jail Museum and Molly Maguires. Compiled by Betty Lou McBride, owner of the Old Jail Museum, September 2014 printing. (This and many other books on the subject, including those used to compile the booklet, are available for purchase in the Old Jail Museum shop.)

The Old Jail Museum on Facebook

Transcript of the Mysteries At the Museum episode featuring the Old Jail Museum's "haunted handprint"

The Old Jail Museum on Paranormal After Party

The Molly Maguires (the film) on Wikipedia

Dublin, Thomas, and George Harvan. When the Mines Closed: Stories of Struggles in Hard Times. Cornell University Press, 1998.

The Molly Maguires markers at the Historical Marker Database: Pottsville and Jim Thorpe

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

Growing up in the Pottsville area the concept of No Irish Need Apply was still in effect in certain places. The Pottsville Club on Mahantongo Street would only have allowed someone like me to enter by the service entrance. When it burnt down the news made the front page of the New York Times, with the suspicion that Patty Hearst had been involved. We referred to the prison as 'Stoney Lonesome'.I went there with my high school class for a tour, but while the rest of the class went through the place I stayed by a cell near the entrance, talking with a young Quaker jailed for non-compliance with the draft. He was in this stone room, with a cot and table and chair, with a thick wooden door with a small barred window through which we talked. I have never meet a person so completely free. Oh, and the film The Molly Maguires played to SRO crowds at the late Capitol Theater in Pottsville, possibly the only place where it did.

ReplyDelete