I found myself unable to update last week because of schedule conflicts, as you may have seen on Facebook. I intended to simply delay the post a day or two, but things just kept getting in the way, so I ultimately decided to delay last week's post until next week. Right now I'm sitting in the house listening to tropical whatever-it-is Ida drop a bunch of rain on my area. The worst weather is expected this afternoon, so it's currently a toss-up as to whether or not I'm going to be able to get to work. But at least I'm doing this work, and once this is live I'll be sending out the monthly email too. If you don't already receive that, please consider signing up with the form on this page! I only bother you once a month and it's free.

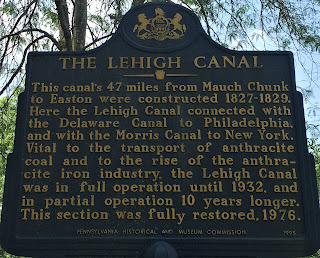

Since I'm already waterlogged anyway, let's take a ride over to Northampton County and visit the Lehigh Canal.

|

| The marker stands in Hugh Moore Park, near the building where canal boat tickets are purchased |

It was Josiah White who came up with the plan for what became the Lehigh Canal (and, a bit later, the Delaware Canal, which has its own series of markers). The canal would run parallel to the Lehigh River and use its water, but in a much more controlled fashion; through a series of innovative locks and gates, the water level could be raised or lowered as needed to allow specially designed canal boats to pass along the waterway. Coal was thus brought to Philadelphia, where it could be sold to merchants throughout the country, and also to Bucks County, where the Durham Furnace needed coal to fuel its iron smelting fires, and to Lehigh County, where David Thomas was using the coal to create anthracite iron in Catasauqua.

I don't know if this is still the case (since it's been quite some time since I was in elementary school and I don't have kids), but when I was in fourth grade, that was the year that our history lessons were centered around Pennsylvania. As part of our lessons, we were taken to Easton, the county seat of Northampton County, to take a ride on a canal boat on the Lehigh Canal. The place is a bit different now, but I took my frequent guest star party member Andrea with me on a visit to what today is Hugh Moore Park, and we rode the canal boat in order to learn about the canals. (Hugh Moore didn't have anything to do with the canal - he's the one who bought the land in order to preserve the green space. He was actually the founder of the Dixie Cup corporation.) Sitting in Hugh Moore Park is the National Canal Museum, with lots of hands-on activities for the kids; being a bit older than the target age range, our interest was more in the canal itself.

As was the case during the canal's 113 years of operation, the boat was pulled by a pair of mules, Hank and George. Our guide explained that Josiah White was an early supporter of animal rights and welfare, and that one of his conditions was that a canal boat operator had to own his own mules - the logic was that if the boat operator owned the animals, he was more likely to take good care of them and treat them well. Hank and George are extremely well tended and very popular with everyone who comes to visit; boat rides are timed in order to give them a good rest in between each one, and for today's inclement weather they've been taken to the same farm where they live during the winter, so they're safe even if the canal floods.

Much of the old towpath is inaccessible today. In addition to the section in Easton, where you can ride the boat (seen at left), portions in Bethlehem and Jim Thorpe have been revitalized as walking trails. The National Canal Museum is a treasure trove of local and state history, and if you get the chance to visit Easton, make sure to drop by and experience it for yourself. And say hello to Hank and George!

(Also, a special hello to my fellow local historian from Catasauqua, Martha Capwell Fox; she works in the archives at the canal museum, and was so kind as to take a break from her work to come down and greet me.)

Sources and Further Reading:

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I would love to hear from you!