I had to delay this week's quest by a day because we had such strong and lengthy thunderstorms yesterday. As my longtime readers know, I'm one of those 'walking barometer' type people and severe weather conditions make me ill. But in one respect this was a good thing: because the post is going up a day late, I get to tell you about something that was posted this morning. Martha Capwell Fox of the National Canal Museum did an article about Laury's Island, using my book as her reference, and gave me a cool shout-out for my work! (I don't know where she found the picture she uses in the article, which I'd never seen, but it's a great image.) Thanks, Martha, you started my day off right!

For this week's quest, after a couple of weeks of visiting new places, we're heading back to some lovely familiar territory in Lancaster. If you're like most people, the mention of a "colonial printer" undoubtedly brings up a mental image of Ben Franklin, churning out copies of Poor Richard's Almanac and issues of the Pennsylvania Gazette. And you're not wrong. But in Lancaster, there was another man whose printing press contributed to the birth of our nation.

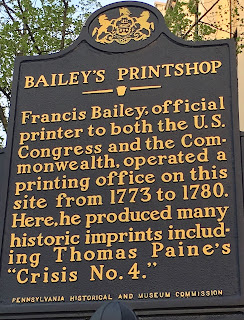

|

| The marker stands at 14 North King Street |

Born in September of 1744 in Sadsbury Township, he was one of at least three children of Robert and Margaret (McDill) Bailey, and the only known son. The family was Scots-Irish Presbyterian, although quite a few of Bailey's later printed materials were in German. As a young man, he apprenticed with Peter Miller and the other printers at the Ephrata Cloister, and in 1771 he opened his printshop and began publishing a periodical called the Lancaster Almanac. Two years later he moved to the shop on King Street, where he would do what may be regarded as his most important work.

His shop's first contribution to the effort for independence was to print Sermon on Tea, a piece by Lancaster writer David Ramsay, who urged people to boycott the British by refusing to drink their tea. This was in 1774. In 1776, he would make an even bigger statement by printing Common Sense, Thomas Paine's famous open call for independence. This wasn't the first edition; that was printed anonymously in Philadelphia earlier in the year. But it counts.

Bailey's biggest assistance to the Revolution came in 1777, when he made the first official printing of a little document called the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. It's usually called the Articles of Confederation for short, and it was our first written constitution - a forerunner to the Constitution. These Articles, which didn't get formally ratified until 1781, gave states individual sovereign authority, while granting Congress the authority to do things like make coins and make treaties. It wasn't a perfect document; it didn't give the government the ability to do things like levy taxes (though your mileage may vary on whether or not that was a bad thing). The proper Constitution would be created later to fill in gaps left in the Articles. Still, they were a good starting place, and Bailey's printing brought them into the public eye. The following year he did a German language version, so that even more people could understand it. Briefly, starting in 1778, Bailey printed a German language newspaper called Das Pennsylvanische Zeitungs-Blat - the Pennsylvania News Sheet - in order to educate German residents of Lancaster about the goings-on in Philadelphia, which had been captured by the British.

With the move to Philadelphia, Bailey's story as it relates to this marker comes to an end. He continued to do official printings for the government; Founders Online even has a letter (see below) sent from him to President Washington, asking for assistance in patenting a new kind of typesetting that would help to prevent counterfeiting. His printshop in Philadelphia was known as "Yorick's Head," because the sign out front depicted Yorick's skull from Hamlet. In 1792, he printed government security certificates for the first opening of the New York Stock Exchange. He also printed currency for Pennsylvania, which was one of the last provinces to print its own money, and was a friend of Ben Franklin's, even serving as witness to a codicil of his will.

Bailey's days of printing in Lancaster have left one other, very sentimental mark on history, because in 1778, he did something which has reverberated in our collective consciousness ever since. He released the 1779 issue of the Lancaster Almanac, and on its cover he described George Washington as Des Landes Vater - literally, "the father of his country." The nickname remains attached to Washington even today; you've likely heard it more than once. Now you know that it first came out of a printshop on King Street.

Sources and Further Reading:

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I would love to hear from you!