Autumn has once again descended on Pennsylvania, with this week and the next expected to bring our peak colors. It's my favorite time of year and I'm hoping to get out this weekend and get some pictures - and not only of markers!

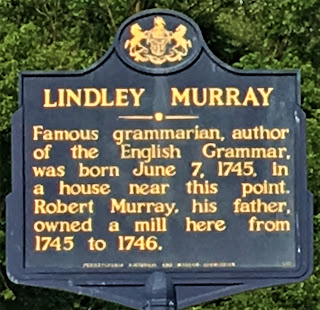

This week's quest is a relatively quiet one, since it's one of those for which I only have a picture of the marker itself. People who know me well may find it an amusing subject for me, though; among my friends and family members I'm known as being a stickler for grammar (that's putting it mildly), and so was today's subject. In fact, he wrote the book.

Lindley Murray was the first of twelve children born to Robert and Mary (Lindley) Murray. His mother was a Quaker; his father, an Irish immigrant, converted when he married her. As the marker says, they owned a mill in the Swatara area for a little over a year. At the age of six, Lindley was sent to school in Philadelphia, where he remained until his family relocated to North Carolina.

In 1753 the growing family moved to New York City, where Robert became a merchant there of considerable repute. The family home was called the Inclenberg, which is a Dutch word meaning beautiful hill. It no longer stands, since the farm was part of what is today Park Avenue, but a plaque erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution marks the place where it stood. The Manhattan neighborhood known as Murray Hill is named for Lindley's parents, and the DAR chapter which erected that plaque is specifically named for his mother. She has her own marker in New York City, as a matter of fact; it's a side quest and we'll get to that in a couple of paragraphs.

Robert tried to make a merchant out of his eldest boy, but Lindley preferred his studies. Working as a teenager in his father's counting house, he actually ran away from home in order to enroll himself in a boarding school in New Jersey. He was found and brought back to New York, although his parents relented and gave him a private tutor. Eventually, Robert's lawyer persuaded him to let his son study law, and he became a practicing attorney in New York.

Robert and most of his family moved to England in about 1764, owing to the patriarch's poor health. Lindley was still in New York; in 1767 he married a young woman named Hannah Dobson, with whom he had no children. They followed the rest of the Murrays to England in 1770, but returned to New York the next year. During the American Revolution, he and his wife spent four years living on Long Island, away from the hostilities.

His mother, on the other hand, at some point returned to the Inclenberg. She was living there in 1776, when - so the story goes - the British General William Howe led his forces to victory at Kip's Bay. He and several of his officers then visited Mrs. Murray, since her husband was a known loyalist, and she (who was not a loyalist, but they didn't know that) entertained them for several hours with cake and wine. This kept them distracted while the surviving continental troops, led by General Putnam, escaped. The whole incident is recounted in the memoirs of James Thatcher, a surgeon who served under George Washington, so it's generally held to be true.

As for Lindley, he went back to practicing law after the war ended, and was so successful at it that he was able to retire in 1783. His health was not good, though; as a child he was never terribly robust, and it's believed that as an adult he suffered from Post-Polio Syndrome. He and his wife Hannah left the United States in 1784 and moved permanently to England, where they settled near York. He maintained a magnificent garden, studied whatever subjects interested him, and amassed an impressive library.

And he wrote.

His first published work was The Power of Religion on the Mind, which was initially published in 1787 and was in its 20th edition in 1842. In 1795 he published his most famous work, English Grammar, which he wrote because he was made aware that there was a distinct need for suitable textbooks for a Quaker school in York. It was so popular that for a long time, it was the only grammar book used in schools in either England or the United States; allegedly, Abraham Lincoln called it the finest book ever placed in the hands of American youth. A corrected edition was released in 1816, and an abridged version in 1818, both of which went through well over a hundred editions each. (This was a Big Deal in publishing.) It was even released in a Braille edition for blind readers and translated for use in India.

He went on to write several more books for use in schools, including a spelling book which was translated into Spanish and books to help English children learn French. Having no children of his own, he gave most of the money he earned from his books to various charities, and in particular was a supporter of William Tuke's work with mental health patients.

Lindley spent the final sixteen years of his life housebound by his illness, and died January 16, 1826. Hannah died September 25, 1834. They're both buried in England. All eleven of Lindley's younger brothers and sisters died before him; however, many of their descendants are still around. Meanwhile, Murray's English Grammar is still being printed in a variety of editions and formats. His family's legacy belongs to New York, and in the end he himself belonged to England - but we had him first.

Sources and Further Reading:

Murray, Lindley, and Elizabeth Frank. Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Lindley Murray: In a Series of Letters. Palala Press, 2015.

Smith, Charlotte Fell. Murray, Lindley: Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 39. Smith, Elder & Co., 1885-1900.

Monaghan, Charles. The Murrays of Murray Hill. Urban History Press, Brooklyn, NY, 1998.

Thatcher, James. A Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783. Richardson and Lord, 1823.

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

In 1753 the growing family moved to New York City, where Robert became a merchant there of considerable repute. The family home was called the Inclenberg, which is a Dutch word meaning beautiful hill. It no longer stands, since the farm was part of what is today Park Avenue, but a plaque erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution marks the place where it stood. The Manhattan neighborhood known as Murray Hill is named for Lindley's parents, and the DAR chapter which erected that plaque is specifically named for his mother. She has her own marker in New York City, as a matter of fact; it's a side quest and we'll get to that in a couple of paragraphs.

Robert tried to make a merchant out of his eldest boy, but Lindley preferred his studies. Working as a teenager in his father's counting house, he actually ran away from home in order to enroll himself in a boarding school in New Jersey. He was found and brought back to New York, although his parents relented and gave him a private tutor. Eventually, Robert's lawyer persuaded him to let his son study law, and he became a practicing attorney in New York.

Robert and most of his family moved to England in about 1764, owing to the patriarch's poor health. Lindley was still in New York; in 1767 he married a young woman named Hannah Dobson, with whom he had no children. They followed the rest of the Murrays to England in 1770, but returned to New York the next year. During the American Revolution, he and his wife spent four years living on Long Island, away from the hostilities.

His mother, on the other hand, at some point returned to the Inclenberg. She was living there in 1776, when - so the story goes - the British General William Howe led his forces to victory at Kip's Bay. He and several of his officers then visited Mrs. Murray, since her husband was a known loyalist, and she (who was not a loyalist, but they didn't know that) entertained them for several hours with cake and wine. This kept them distracted while the surviving continental troops, led by General Putnam, escaped. The whole incident is recounted in the memoirs of James Thatcher, a surgeon who served under George Washington, so it's generally held to be true.

As for Lindley, he went back to practicing law after the war ended, and was so successful at it that he was able to retire in 1783. His health was not good, though; as a child he was never terribly robust, and it's believed that as an adult he suffered from Post-Polio Syndrome. He and his wife Hannah left the United States in 1784 and moved permanently to England, where they settled near York. He maintained a magnificent garden, studied whatever subjects interested him, and amassed an impressive library.

And he wrote.

His first published work was The Power of Religion on the Mind, which was initially published in 1787 and was in its 20th edition in 1842. In 1795 he published his most famous work, English Grammar, which he wrote because he was made aware that there was a distinct need for suitable textbooks for a Quaker school in York. It was so popular that for a long time, it was the only grammar book used in schools in either England or the United States; allegedly, Abraham Lincoln called it the finest book ever placed in the hands of American youth. A corrected edition was released in 1816, and an abridged version in 1818, both of which went through well over a hundred editions each. (This was a Big Deal in publishing.) It was even released in a Braille edition for blind readers and translated for use in India.

He went on to write several more books for use in schools, including a spelling book which was translated into Spanish and books to help English children learn French. Having no children of his own, he gave most of the money he earned from his books to various charities, and in particular was a supporter of William Tuke's work with mental health patients.

Lindley spent the final sixteen years of his life housebound by his illness, and died January 16, 1826. Hannah died September 25, 1834. They're both buried in England. All eleven of Lindley's younger brothers and sisters died before him; however, many of their descendants are still around. Meanwhile, Murray's English Grammar is still being printed in a variety of editions and formats. His family's legacy belongs to New York, and in the end he himself belonged to England - but we had him first.

Sources and Further Reading:

Murray, Lindley, and Elizabeth Frank. Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Lindley Murray: In a Series of Letters. Palala Press, 2015.

Smith, Charlotte Fell. Murray, Lindley: Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 39. Smith, Elder & Co., 1885-1900.

Monaghan, Charles. The Murrays of Murray Hill. Urban History Press, Brooklyn, NY, 1998.

Thatcher, James. A Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783. Richardson and Lord, 1823.

Added January 2023: The Murray Schoolhouse in Lebanon County, named after Lindley Murray. YouTube video by the Hometown Historian.

Lindley Murray at the Historical Marker Database.

Lindley Murray at the Historical Marker Database.

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I would love to hear from you!