Before I sink my teeth into this week's post, let me draw your attention to the snazzy new header image, designed by my friend Rachel - I love it so much! Check out the quest links page if you'd like to contact her about her graphic designs. Thank you, Rach!

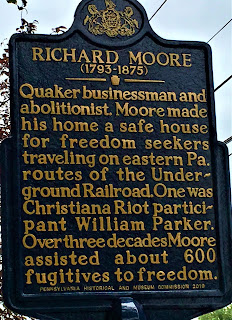

Last week, I told you about the fun I had watching this marker be unveiled and dedicated. This week, we'll actually talk about what's on the marker, and the history which led to it.

Last week, I told you about the fun I had watching this marker be unveiled and dedicated. This week, we'll actually talk about what's on the marker, and the history which led to it.

I recently had a conversation with my mother about history. Apparently, some public school students we know were never taught about the Underground Railroad in school, and neither of us can figure out why. Part of the reason it's so important for us to learn about our history is so that we can learn from our history, or else mankind is just doomed to keep making the same mistakes. I don't generally get political on this blog, for what I would imagine are fairly obvious reasons, but I also don't think it's exactly a major political statement when I say that slavery is wrong, and is one of the big mistakes that we need to learn not to repeat.

|

| The marker is situated on the front lawn of Richard Moore's home at 401 South Main Street, Quakertown. (Yes, you get to see it this week.) |

(If you're not from eastern Pennsylvania, you probably mostly recognize the term from Quaker Oats, which features an image of a kindly elderly gentleman in a funny hat on the front of the packaging. Said gentleman is believed to be inspired by old woodcuts of Pennsylvania's founding father, William Penn, who was himself a Quaker. Quaker Oats and the Religious Society of Friends are not and never have been affiliated, but the oatmeal company chose the name because they wanted to be associated with values embraced by the Quakers, like integrity and honesty.)

Anyway, Richard Moore was a Quaker. Born in Montgomery County in 1793, he relocated to Richland Township in Bucks County in 1813, where he became a schoolmaster. At that time, public schools as we know them today did not exist; parents had to pay for their children's education in one of a few ways, such as by a private tutor or in a parochial school affiliated with their church. Parents who could not afford such a thing could only send their kids to what were known as "pauper schools," which sound like something out of a Dickens novel. (Actually, considering the time period, it very possibly was.) Our friend Richard was a teacher of several such children.

|

| Richard Moore's house (with its shiny new marker) on the day of the marker dedication |

In 1819 he married Sarah Foulke, a member of a prominent local family. They had two children, John Jackson and Hannah, and by 1833 Richard had stopped working as a teacher and taken up the life of a potter. A man called Abel Penrose had opened a pottery just outside of Quakertown, and Richard took over the business and continued to operate it with his son for the next several decades. The following year, he bought the property where the pottery was situated and built a beautiful house next to it. The pottery has since been torn down, but the house remains standing on what is today Main Street in Quakertown; the nearby cross street is named Moores Court in his honor.

Of course, none of that really has to do with why he has a historical marker. I just wanted to give my readers a sense of who he was as a person. He was devoutly religious, a husband and father, a hard worker, a property owner, a successful businessman. And he was a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Suffice it to say that the vast majority of Quakers were opposed to slavery. That's a bit of a simplification, but it'll serve the purpose. According to Eric Foner, whose study is cited in Richard Moore and the Underground Railroad at Quakertown, Quakers were generally considered different from other whites in the eyes of black people; one escaped slave, James Williams, received advice from a free black man here in Pennsylvania that he should not trust any white person - except the Quakers. As such, quite a few Quakers assisted runaway slaves and helped with the Underground Railroad, and Richard Moore was in fact one of the better known examples of a Quaker conductor. His home's location in upper Bucks County made it the most active 'station' in the area, in part because of how close it was/is to Philadelphia and also to the Blue Mountains, where many escaped slaves found it easier to hide in the wilderness.

|

| Street sign at the intersection near Richard Moore's house |

Richard's grandson, Alfred Moore, spent his childhood in that same house while his grandfather was assisting runaway slaves. In interviews as an adult, he said that as early as the 1830s, it started to be known as an Underground Railroad station. In addition to helping slaves in the process of escaping, Richard also aided those who had already escaped, but were tracked down by their former masters.

This is how it was described during the dedication ceremony for the Moore marker. Pennsylvania was a free state, meaning that people here could not own slaves. However, if a slave owner managed to track down his escaped slave, he was entitled by federal law to come and collect his 'property' and take them back home. This was part of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. The federal law, of course, overruled the state law, so Pennsylvania residents weren't supposed to interfere in such a collection. That's why being a conductor on the Underground Railroad was so dangerous - it meant breaking federal law. This, as one might expect, led to a number of less than pleasant interactions where the escaped slave wasn't lucky enough to evade his or her former master; the Christiana Riot, mentioned on Richard's marker (and the subject of a future blog post), was such an incident. Some conductors were arrested for their involvement.

|

| The Richard Moore house viewed from the north side |

Richard died at home on May 28, 1875, ten years after the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution (outlawing slavery) was ratified and ended his tenure as conductor. He and his wife Sarah are both buried in the Friends Meeting cemetery. His son John Jackson continued to operate the family pottery for a few more years before retiring; he married and had three children. Daughter Hannah also married and had two children. However, none of Richard's five grandchildren ever married or had children of their own, so he has no living descendants, which accounts for the fact that the house no longer belongs to the family. It currently belongs to Steven and Virginia Papiernik, who purchased it in 2002 and began to renovate it, revealing and restoring the original look of the building. It's not open to the public, because it's a private residence; but the Papierniks joined the local effort to put a marker on their lawn, and it was approved in 2018.

I think that I'm not going to find a better way to end this post than by quoting from Richard Moore and the Underground Railroad again. It's just too well written, and I hope Dr. Leight and Mr. Moll don't mind.

The marker is an appropriate reminder of an era when men and women of conscience practiced civil disobedience to help fellow human beings. It reminds us of Richard Moore, a humanitarian who not only saw injustice but also found ways to combat it.

Sources and Further Reading:

Leight, Dr. Robert L. and Thomas Moll. Richard Moore and the Underground Railroad at Quakertown. Tohickon Publishing, Quakertown, 2019.

Program from the dedication ceremony of the Richard Moore historical marker. Published by the Quakertown Historical Society, September 14, 2019.

Author unspecified. "Commemorative Historical Marker Unveiled at Richland Quakers’ Richard and Sarah Moore’s Home." Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (PYM) of the Religious Society of Friends, September 16, 2019.

Asaris, Eric. "Underground Railroad hero to be honored with historical marker in Quakertown." WFMZ News, July 10, 2019.

The African-American Museum of Bucks County

Tour the Underground Railroad in Bucks County, including Richard Moore's house

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

Back in 1990, my husband and first daughter and I lived in this house. It had been made into apartments at the time. We lived in the middle section which was a 2 bedroom. I have some wonderful happy memories of us living there. We moved out in 1992 when I got pregnant with my second daughter. I still drive by sometime when I'm in the area just for nostalgia sake I guess.

ReplyDeleteHow neat to hear from someone who once lived in the house! Thank you so much for reaching out!

Delete