I am alive and returned from Zenkaikon! Hello to everyone who is new to the blog - I actually ran out of my business cards during the Lancaster history panel, so if any of you found your way here because of that, I'm very happy that you've joined us.

If you read the most recent newsletter, you know that my computer is in need of a little TLC; I haven't had the chance to take care of that yet. But the main reason for a lack of posts this month is because almost every waking moment has been spent either at my actual job or preparing, in one sense or another, for my beloved convention. My panels went well, I think, and as ever I had a marvelous time. The only disappointment was that we were so busy with our friends and the many activities that I never had the chance to go marker hunting, even on the way home! But my emotional support silly man did record my panels for me, so next week (once he's had the chance to get them off of his phone) I'll be sharing the ghosts of Lancaster with all of you.

Also, for those of you who didn't see it in the newsletter or on the Facebook page, my non-convention excitement of recent weeks was being interviewed! Paula, the Keystone Wayfarer, is a fellow Pennsylvania blogger and she cites MarkerQuest as one of her inspirations, which touches me so deeply you don't even know. She really makes me sound like a big deal in her article, which can be read here, and definitely do yourself a favor and check out her other posts as well because she's awesome.

Meanwhile, trying to get back to what I do here, let's take a trip down to scenic Berks County and learn something, shall we?

|

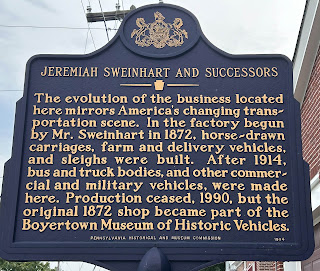

| The marker stands at the intersection of Third and Walnut Streets, on Third Street |

Jeremiah's venture was quite successful - so much so that he was able to retire after just twelve years of it. He advertised in the Democrat of his intent to sell, and out of all those who responded to the ad, he selected two - Milton Strunk and Horace Fisher - and handed off the carriage reins to them. Two years later, though, Fisher sold his half of the partnership to Frank Hartman, a twenty-year-old carriage builder who, like Strunk, was from Milford Township in Bucks County.

Now operating under the name of Hartman & Strunk, they turned Jeremiah's original shop into their blacksmith workspace and built a three-story carriage shop near what is now Third Street. Later they also added a winter storage facility, connected to the factory by a wooden ramp, and a third story which served as a paint shop. Strunk sold his share of the business to Hartman in 1890, and the business name changed to F. H. Hartman Carriage Works. He began expanding the production line; in addition to the previous offerings from Jeremiah Sweinhart's time, the factory also produced wagons for bakeries, milk, ice, and ice cream, among other commercial vehicles. In the early 1900s, the carriage works was outfitted with electricity, including a pair of electric motors for the milling and shaping machines and a modern electric forge.

What Strunk did immediately after selling his share, I couldn't tell you; but when the Boyertown Burial Casket Company opened in April 1893, he took the post of general superintendent. If you've read my other posts from Boyertown, you can probably see where this is going. In 1908, the town was devastated by the Rhoads Opera House fire, one of the deadliest fires of the 20th century. 171 residents of Boyertown were killed that night or died shortly afterward from their injuries. For the next week, the carriage works was shuttered, as was every other factory in the community - except, of course, for the casket company, which was working overtime.

In 1911, Hartman (who by this point had renamed his business the Boyertown Carriage Works) announced his intention to retire. Four of his longtime employees - Morris Gilbert, Milton Derr, Al Shuler, and John Landis - pooled their resources to buy the business. Hartman stayed on for one more year to ease the transition and mentor them in the buying and selling parts of running the outfit, since the four men were all from the manufacturing side of things, and they slightly renamed their establishment Boyertown Carriage Works, Ltd.

Henry Ford's method of mass producing automobiles, and their growing popularity even with farmers, naturally required the carriage manufacturers to change with the passage of time. By 1918, gasoline-powered truck chassis formed the bases of the majority of their products, but by 1926, it was clear that they needed to change their output to the more modern designs. Shuler and Landis had long since parted ways with the company, and Derr and Gilbert weren't terribly interested in abandoning the carriage manufacturing which had been their lives' work. They sold controlling interest in the company to a group of investors from the city of Reading, led by Frank Hafer, Howard Swartz, and George Hoffman.

The new owners changed the name of the business for the final time, dubbing it the Boyertown Auto Body Company. They began experimenting with novelty vehicles, unusually shaped trucks meant to advertise as well as deliver product. There were vans shaped like loaves of bread for bakeries, a truck shaped like a bottle of milk for the Mowrer Dairy in Bethlehem, and even a cargo box shaped like a box of Luden's cough drops for that company in Reading. The three-story woodwork and paint workshop, the one Hartman & Strunk built back in the 1880s, caught fire in 1932 and was replaced by a brick structure, measuring 5,000 square feet and outfitted with individual spray booths for painting vehicles.

Swartz sold his share of the firm to Frank Hafer and his son, Paul Hafer, in 1933, and a year later they bought out Hoffman as well. Both men had grown wary of continuing to run a business in the Depression, so the company turned into a Hafer family project. They emerged from the Depression with a strong company, and continued to adjust their products to move with the times. The bodies of what would become Fords, Chryslers, and even Mack trucks rolled off of their assembly lines. They were even credited with devising the name of the Chrysler Town & Country, which debuted in 1941.

When the United States entered World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, more than sixty employees of the Boyertown Auto Body Company served in the Armed Forces, with many of their wives taking their places on the factory floor. The entire facility was devoted to supporting the war effort, making ambulances and mobile shops for machinery, uniform repair, dental prosthetics, radio communications, and tire repair. In gratitude, the factory was given the prestigious Army-Navy Award for Excellence in War Production, known familiarly as the "E" award.

Following the war, they returned to making commercial vehicles, which were now more in demand than ever; with metal in short supply until nearly 1950, they had to go back to using wood for some of their products. The company's footprint continued to expand, adding an export office in New York City and a storage facility in Reading. Their catalog also continued to expand, as the television industry started to gain traction and the Boyertown facility was among the first to produce electronic field production bodies for it. They were contracted to build delivery trucks for the postal service, as well as fire and rescue vehicles, bookmobiles, and mobile canteens. The Boyertown Trolley Company relied on them for vehicles. They even received a commission in 1951 to build a special Tour Wagon, their camper, for Prince Makonnen, son of the Ethiopian emperor.

You can still visit the workshop, however. In 1965, Paul Hafer and his wife Erminie established the Boyertown Museum of Historic Vehicles. After the factory closed, the museum acquired both the main building at 85 South Walnut Street. It now serves as the primary museum, and contains many of the carriages, trucks, and other vehicles that were produced in that very building. The museum also includes the reconstructed Fegley's Reading Diner (note that it doesn't serve food) and a 1921 Sunoco gas station. Additionally, Jeremiah Sweinhart's original workshop on Philadelphia Avenue is still standing and part of the museum complex; visitors can view a reconstruction of his forge and belt-driven machine shop. Please visit the official website, linked below, for museum hours, prices, events, and other information.

Sources and Further Reading:

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I would love to hear from you!