It looks like a lot of people are taking interest in the "fiveaversary" scavenger hunt, and I'm excited about it! I've shared a few clues on the blog's social media outlets already, so if you're not already following the Facebook or Twitter, definitely hop over there to read those. Meanwhile, here's a clue for everyone: The answers to questions #7 and #15 have the same first name, and that's pretty much the only thing they have in common. You've got just two more weeks to submit your answers - good luck!

As for the quest, I said last week that it was the final week of not repeating a county this year. I was wrong! I was recently able to take a couple of unexpected side quests and add a bit more to my list of captured markers. This past Sunday, the plans that I had with my youngest sister Liza were upended, and she surprised me by proposing we go and collect some markers instead. We had an excellent day in Doylestown, where we toured the Mercer Museum and she delighted the docent with her exclamation of "Wow!" upon seeing the central room. After that we visited Peace Valley Lavender Farm, which was new to us both; her whole car smelled like lavender for the rest of the day from everything we bought. Following lunch, we had some delicious ice cream at Evolution Candy on State Street. Before heading home, we went to Le Macaron Doylestown, on Oakland Avenue, and treated ourselves to gourmet cookies. (Hi Steve! Thanks for the Facebook follow!) I definitely recommend all of these places for the next time you're in the area, and I particularly recommend the lemon macarons, which were divine.

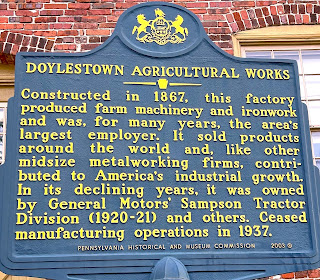

And I managed to get five markers, which means I've got almost all of the Doylestown markers now, and today we're going to look at one of them.

|

| The marker stands on Ashland Street just outside of the old Works plant |

By 1851, the shop began making other things. I'm not very well-versed in farm equipment, so I can only go by what I'm reading in my source materials. It's specifically noted that the Works was the first business in Bucks County to build "Wheeler's Patent Railway Chain Horse Power, Overshot Thresher, Feed Cutter, and Clover Huller." If your response to that is "What?" then I feel better because I'm not alone. Even Google couldn't explain to me exactly what that was. Whatever it was, it was made in Doylestown.

Melick and Hulshizer sold their business after the first decade of profits, in 1859, to Martin V. Wetherill. This gentleman ran the Works for six years, and then sold it back to original owner Daniel Hulshizer. (I can't find a record of Melick's first name.) Daniel built "a large plant on Ashland Street near the Railroad Station." He enlarged the building before very long and, in addition to the existing catalogue, began also manufacturing upright steam engines. In 1876, the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition awarded a first-prize ribbon to a device patented as the Doylestown Thresher, which was capable of threshing a variety of crops including wheat, peas, beans, straw, and peanuts.

By 1884, products offered exclusively by the Works included the Doylestown Excelsior Patent Horse Power, the Doylestown Thresher and Shaker, the Doylestown Junior Thresher and Cleaner, and the Doylestown Triumph Horse Power, among others. Two years later, the company's repertoire expanded yet again as they began making machines to be used in creameries.

The Hulshizers continued to operate the business until near the end of the 19th century. In 1899, Daniel's son W. Sharp Hulshizer sold the company to Henry D. Ruos, the proprietor of a business called the Lenape Bicycle Works, and the Works became registered under the name of Ruos, Mills and Company. In 1903 they enlarged the plant in order to build farm machines of their own designs, including three brand new creations that had been originated entirely in-house - the ensilate cutter and elevator, the riding cultivator, and an improved corn sheller.

In 1907, the Works was incorporated as the Doylestown Agricultural Company, Inc., and as the 20th century got underway, it became the most important industry in the entire Doylestown region. An export sales office, situated at 30 Church Street in New York City, handled their international sales; Doylestown products were shipped overseas, with both Israel and Peru being remembered as buyers. The business expanded beyond farm equipment and began creating specialty iron crafts. Many benches and wrought iron fences found in parks in Philadelphia, New York, and Atlantic City were manufactured in the Doylestown plant. The company received multiple offers to relocate their headquarters to other states, but refused them all.

The invention of the combine, which both harvests and threshes crops simultaneously, caused the company's major product - the thresher - to become obsolete. In 1920, General Motors bought 90% of the company's stock in their efforts to compete with Ford Motor's agricultural machinery department. They had the Doylestown factory churning out tractors, but this proved unprofitable. The company bought back its stock in 1921 and resumed making farming machines and specialty iron crafts. That same year, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was established in Arlington National Cemetery, and the Doylestown company received the biggest feather in its historical cap: they were commissioned to make the bronze gates which surround the Tomb.

The Great Depression saw a temporary end to foundry operations in 1937. Though the company continued to build machinery out of extra parts, they primarily survived by providing repairs to existing farm vehicles and equipment. After World War II, operations resumed, but the end was nearing all the same. Farming was no longer a dominant industry, and finally, in 1968, the Works closed its doors.

Today, the Works building is part of the Francis D. Shaw Block on the National Register of Historic Places. The Shaw Historic District includes buildings constructed between 1833 and 1914, and also includes a number of houses and the Rhodes Livery Stable. It's part of the Doylestown Historic District. Since 1985, the Works plant has been home to several offices, shops, and a restaurant, following a $2 million renovation. But lest anyone forget the building's origins, the lobby has a display of some of their smaller machines, including the Doylestown Junior Thresher and Cleaner, as well as enlarged copies of pages from a farm catalogue showing some of the other pieces that were once made in the heart of Doylestown.

Sources and Further Reading:

Official website of the Doylestown Historical Society

Levenson, Edward. "Why Does the Doylestown Agricultural Works Include Former Houses?" The Doylestown Patch at Patch.com, December 2011.

Fletcher, Stevenson Whitcomb. Pennsylvania Agriculture and Country Life, 1840-1940. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1955.

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I would love to hear from you!