Today, we're taking a look at the most famous resident of my Lehigh County hometown of Catasauqua. He had two different houses, and thus has two different markers, but I've never actually managed to see the one in Northampton County. Despite living in the same county, I don't get to Easton very often. Luckily, my biggest fan was in Easton some weeks ago and took some pictures for me, so I get to add another name to my list of guest photographers.

|

The marker is situated on the front lawn

of the Catasauqua estate, near the intersection

of Lehigh and Poplar Streets

|

You can't grow up in the Catasauqua school district without learning about George Taylor. You just can't. He's the most famous person ever to have lived in the borough, and likely always will be, because it's hard to outdo someone who signed the Declaration of Independence.

It's known that George Taylor was born in Ireland in 1716, the son of a minister; he was twenty years old when he immigrated to what would eventually be the United States, arriving at the Port of Philadelphia in 1736. His passage was financed by Samuel Savage, Jr., an ironmaster in Bucks County, so young George was an indentured servant to pay off the debt. This wasn't particularly unusual.

Edited 2/22/2023: Deb of the Historic Catasauqua Preservation Association informs me that research has indicated George was not an indentured servant as previously believed. Thank you for this clarification!

By all accounts, he started off as a laborer in Savage's employ; Savage owned Warwick Furnace and Coventry Forge, and when he learned of George's educational background, he promoted him to the position of bookkeeper. This was also not unusual.

What was unusual was the actual outcome of his servitude. Savage died in 1742, leaving behind a widow, Ann, and at least one minor child, Samuel III. Less than a year after Savage's death, George and Ann were married. You can probably imagine this was a bit of a scandal at the time; Ann's relatives were not at all pleased that she didn't complete a full year of mourning before remarrying, as was the societal norm. (Interestingly, Ann's maiden name had actually been Taylor, although there's no indication that she and George were related.) The details of the arrangement remain fuzzy, but we do know that George took charge of the two ironworks for the next ten years. By all accounts he ran them well until Samuel III came of age and, according to the terms of his father's will, became the new ironmaster. The industry was handed off to the son without known issue, and George and Ann continued to live at Warwick Furnace for a few more years. He and Ann had two children together; their daughter Ann, nicknamed Nancy, died in childhood. Son James was born at Warwick Furnace in 1746.

|

19th century illustration of

George Taylor, based on his

portrait, displayed at the

George Taylor House |

In 1755, George entered a partnership with some other investors to lease

Durham Furnace, in Upper Bucks County. His partners included William Allen, the founder of Allentown, and a few of Pennsylvania's other most influential men. In addition to being ironmaster, George became a justice of the peace in Bucks County from 1757 to 1763, at which time the lease for the furnace expired. He and Ann then moved to Easton, in Northampton County, where he owned and operated a tavern; he again became a justice of the peace in his new county, and with the support of William Penn he was elected to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly.

It was around this time that he became important to Catasauqua school children, not that he knew it. He purchased a large plot of land on the banks of the Lehigh River, in what was then known as Biery's Port, and constructed a beautiful Georgian mansion. The house was completed in 1768, and George and Ann moved in; James had studied law and married a young lady named Elizabeth Gordon, and they remained in Easton near her family. Unfortunately, not long after they took up residence in their two-story stone home, Ann Taylor died.

George was left alone in the big house with his servants. Among these was Naomi Smith, his housekeeper. It wasn't exactly unusual for the time that he gradually became 'involved' with her, and they eventually had five children together. He was still serving in the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly at the time of Ann's death, and remained in the house for a few years while leasing half the property for farming purposes. He intended to stay there, and bequeath the home to his son James, who had moved with his family to Allentown. Unfortunately, James died in 1775, putting an end to George's plans for the Catasauqua mansion.

|

| The George Taylor House in Catasauqua, west face |

He sold the house in 1776 and moved back to Durham Furnace. By that time he had been re-elected to the Provincial Assembly and was also commissioned as a colonel in the Third Battalion of the Pennsylvania Militia, since it was increasingly clear that the colonies were going to war for their independence. When the five Pennsylvania delegates to the Continental Congress were forced to resign in 1776 because they were all loyalists, George was one of the replacements elected, and got to put his signature on the Declaration of Independence. Of the 56 men who signed the document, he was the only ironmaster and the only one who had ever been an indentured servant, and one of only eight who had not been born in the colonies.

From there, George gradually became more obscure. When a new Pennsylvania delegation to Congress was appointed in February 1777, he was not re-nominated to his post. Instead, he was appointed to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, and participated in the daily meetings to help govern the fledgling state under the new constitution. Although he attended these meetings faithfully for the first month of his tenure, he became extremely ill in April and was bedridden for several weeks, after which he decided to retire from the council for health reasons. Though he continued producing cannon shot and shells at Durham Furnace for the Continental Army and Navy, one of his partners, Joseph Galloway, fled to England; he was convicted as a traitor and the Assembly seized his properties, including Durham Furnace.

|

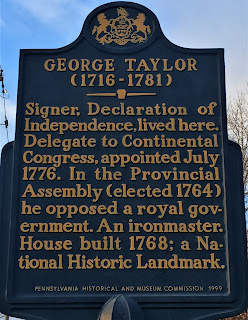

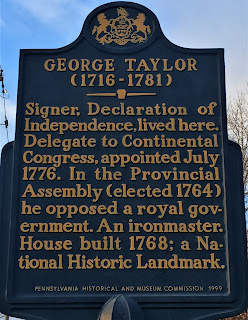

The marker stands in front of the house at the

intersection of South Fourth and Ferry Streets, Easton.

Image courtesy of Kevin Klotz. |

George was able to file an appeal that let him finish out the first five years of the property's lease, but it was then sold to a new owner. He joined another partnership to lease the Greenwich Forge in New Jersey, but he recognized that his health was becoming an even greater concern and returned to Easton, where he moved into a fine two-and-a-half story Georgian style home at South Fourth and Ferry Streets.

The home, which was built between 1753 and 1757, was originally constructed for William Parsons, an English immigrant who had represented Northampton County in the Provincial Assembly. He died in the house in December 1757, aged just 56 years old, from a mixture of illness and grief at the death of his eldest daughter from consumption. He was known as "the Father of Easton" because of all he had done for the city, ranging from librarian to Surveyor General.

|

The Parsons-Taylor House in Easton.

Image courtesy of Kevin Klotz. |

It was into his home that George Taylor moved in 1780 with his small household. He died there in December of 1781, and was buried in a churchyard, then later reinterred in the massive Easton Cemetery with a considerable memorial to mark the site. He left behind Naomi Smith and the five children they had together - Sarah, Rebecca, Naomi, Elizabeth, and Edward. He also left his five grandchildren, the children of his son James - George, Thomas, James Jr., Ann, and Mary. According to his will, $500 each was left to Naomi Smith and his eldest grandchild George, and the rest of his property was to be divided equally between the other children and grandchildren. However, because of the financial difficulties and legal entanglements brought about by disputes over the Durham and Greenwich Furnaces, the estate was declared insolvent and the terms of his will were never fulfilled.

Apart from his signature on the Declaration of Independence, the two houses remain George Taylor's biggest legacy. The Easton home, known today as the Parsons-Taylor House, passed through various hands until 1906, when it was purchased by the Daughters of the American Revolution. Since that time it has served as the headquarters of what is known as the George Taylor chapter of the organization. My husband Kevin had to go to Easton for jury duty selection in December 2020, and brought home pictures of the house and marker. The building is open to the public, but only on guided tours by appointment, although they also open their doors for Easton's Heritage Day each July (well, under normal circumstances).

As for the house in Catasauqua, George sold it to John Benezet, a Philadelphia native who served a secretary for the Pennsylvania Provincial Congress. He later also served on Philadelphia's Committee of Correspondence and as Commissioner of Claims in the Treasury Office. He returned to his business ventures in 1778, and was declared dead in the winter of 1780 when his ship was lost at sea on its way to France. His widow sold the Biery's Port estate to David Deshler for the same amount for which her husband had purchased it from George Taylor. David Deshler was the son of Adam Deshler, whom my readers may recall built

Fort Deshler in what today is Whitehall. Through a series of excellent business practices, David Deshler became one of the wealthiest men in the county, and also served in the Provincial Assembly. After retiring from public service, he settled in the Catasauqua mansion and died there in 1796.

The estate more or less languished until 1945, when it was rescued and resurrected by the Lehigh County Historical Society. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1971, and for many years the Borough of Catasauqua "rented" the property from the Historical Society for the price of a single red rose, presented annually on the Fourth of July. I remember attending one such rose ceremony several years ago. In 2008, the society sold the house and its attendant five acres of land to the borough, and the property has been under the care of the George Taylor House Association for several years. The rooms are outfitted with period furniture and even include a fireplace plate from one of George Taylor's own ironworks (seen at left). The museum is open for special events, including a recurring open house, and the association members are thrilled to share their knowledge of the house's history with the public; they were very welcoming when I attended the open house in November. An ongoing excavation of the kitchen wing has unearthed many artifacts from the years of the house's colonial occupation, which are on display under glass, and it's hoped that even more of the property's unique history will be uncovered in the coming months.

Both of George Taylor's residences will welcome your interest, so please check out the links below in order to find out how to visit!

Sources and Further Reading:

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

I think it has been concluded that GT was never an endentured servant. An early historial got that wrong. For more recent research, ck out the GT, Esq history published in 1968 by Mildred Rowe Trexler of the LCHS.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this info, Deb! I've updated the post accordingly and credited you for it.

DeleteHello Deb. I am George Taylor’s grandson. He is my brothers and my 5th great grandfather. His middle name was William and nearly every generation from then to now has a male descendant named William! Feel free to contact me at rickhudgell@gmail.com. My brothers and I are hoping to visit the George Taylor house this summer

ReplyDeleteHello Anonymous. I too am a descendant of George Taylor, he is my 7th great-grandfather. The only middle name I have ever found was "Edmund" and from what I've read, that name has never been confirmed. Supposedly there is no documentation of George's middle name. If I may ask, how did you come about the name of "William" as his middle name? Thanks you.

ReplyDelete