Just like my last post contained an admission that I'm not exactly a devotee of football, this one contains an admission that I'm also not into fishing. Unless it's a fishing minigame in one of my video game adventures, you're not likely to find me holding a rod and reel.

Some of my friends went to Easton last year for their annual Garlic Fest. My best friend Andrea was of the party, and she texted me photos of a couple of markers from near the festival, one of which is today's subject. I remember getting this one and thinking it was something of a strange topic to honor on a historical marker - but as I've repeatedly had cause to discover, I am not as smart as I like to think I am.

Fishing, as some sources tell me, isn't just a sport but also a science. I guess that makes sense if you think about it. The construction of fishing equipment has to be just so in order to bring in the different weights of catch. And even today, fishing enthusiasts are indebted to the scientific work of a man named Samuel Phillippe.

Sam - I'm going to call him Sam because I am nothing if not lazy - was born in Reading, Berks County, in August of 1801. He didn't start out making fishing rods; he moved to Easton in 1813, when he was just twelve years old, and was apprenticed to a gunsmith named Peter Young. As an adult, he opened his own shop, and gained a reputation for being a quality gunsmith and locksmith. Above all, though, he was an excellent mechanical engineer, and his tinkering eventually led him in other directions as well. In particular, it meshed with two of his hobbies.

One of these hobbies was music. Sam became a violinist, both playing and crafting violins. In 1846, one of his instruments won an award at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, a place I have visited many times. According to the Journal of the Franklin Institute, Sam's violin was "pronounced by competent judges to be of excellent quality, and will improve with age. This being a new branch of manufacture, and the finish and quality of this instrument so good, the judges recommend the award of First Premium."

His other hobby, the one which forms the focus of the marker (and therefore this post), was fishing. At the time, fishing was a huge recreational activity in Pennsylvania, and had been for decades; William Penn himself had praised the many different kinds and sizes of fish to be found in Penn's Woods, and the settlers who came to his wilderness were pleased with what they found in the waterways. By the time Sam had set up shop in Easton, fishing had become such a widespread hobby that the city of Philadelphia had no less than four social clubs devoted to it. One of these was the Schuylkill Fishing Company, which was established in in 1732 and included President George Washington as one of its honorary members; the Company is still around today, and claims the title of the oldest continuously operating social club in the United States, if not the world. So fishing was regarded as not only fun and relaxing, but somewhat prestigious.

Sam greatly enjoyed trout fishing, and therefore knew firsthand the challenges which came with the sport. So he started making his own rods from a variety of woods - hickory is the only one I recognize, but he also used fantastical-sounding elements like greenheart, snakewood, lancewood, and lemonwood. Not altogether satisfied with any of them, he turned to using cane, experimenting with the processes of rending and laminating it in the style of English bowmakers. He continued his experiments, finally perfecting a six-strip cane rod around 1848. It's believed that he most likely used Calcutta cane, from India.

Sam was married twice and had two sons, Daniel and Solon; I found a reference to a daughter in one obscure source, but it gave her no name, and his record at FindAGrave.com doesn't indicate any other children. Daniel died as a young man and, as far as I can tell, never married. Solon served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and worked with his father making fishing rods. By 1859, they were making split-cane rods with laminated hardwood and bamboo grips. Sam and Solon formed a company in or around 1873, based on North Second Street, and advertised their services as being "Dealers in guns, pistols, powder. Bamboo and cane poles & joined poles made to order. Sewing machines, locks, etc. repaired and keys made to order." The company moved four years later to South Third Street, where the marker stands today; the building is, as of this writing, a Wells Fargo bank.

Sam passed away from pneumonia in May 1877, not long after the company's relocation to Third Street, and there was a fair bit of public mourning for the loss of the locksmith, violin maker, and fishing rod master. Solon continued to operate the business after his father's death, dying himself in 1925; he, his father, mother (or stepmother, it's not clear), and brother are all buried in the Historic Easton Cemetery.

Bamboo rods dropped out of popularity in the 1950s, because of President Truman placing an embargo on Chinese imports (making it almost impossible to get bamboo for a long time) and also because of the introduction of fiberglass rods. Easton's Sigal Museum has one of Solon's fishing rods in its collection, but as far as anyone can tell, none of Sam's rods survive to this day. But a good bamboo rod isn't hard to find, and I even found a number of tutorial videos on YouTube which instruct you in making your own. I think Sam would approve.

Sources and Further Reading:

Parkhill, S. M. "Easton developed the pole that has evolved into what is used today." The Allentown Morning Call, May 8, 1997.

Sajna, Mike. Days on the Water: The Angling Tradition in Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1999.

Author unspecified. Journal of the Franklin Institute, Vol. 41-42. Pergamon Press, 1846.

Samuel Phillippe at TheHistoricEastonCemetery.org

Samuel Phillippe at FindAGrave.com

Samuel Phillippe at the Historical Marker Database

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

|

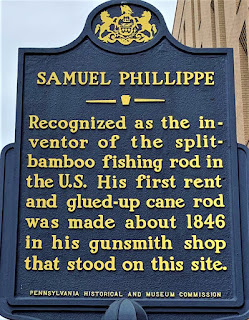

| The marker is situated at the intersection of South Third and Pine Streets. Image courtesy of Andrea Gillette. |

Sam - I'm going to call him Sam because I am nothing if not lazy - was born in Reading, Berks County, in August of 1801. He didn't start out making fishing rods; he moved to Easton in 1813, when he was just twelve years old, and was apprenticed to a gunsmith named Peter Young. As an adult, he opened his own shop, and gained a reputation for being a quality gunsmith and locksmith. Above all, though, he was an excellent mechanical engineer, and his tinkering eventually led him in other directions as well. In particular, it meshed with two of his hobbies.

One of these hobbies was music. Sam became a violinist, both playing and crafting violins. In 1846, one of his instruments won an award at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, a place I have visited many times. According to the Journal of the Franklin Institute, Sam's violin was "pronounced by competent judges to be of excellent quality, and will improve with age. This being a new branch of manufacture, and the finish and quality of this instrument so good, the judges recommend the award of First Premium."

His other hobby, the one which forms the focus of the marker (and therefore this post), was fishing. At the time, fishing was a huge recreational activity in Pennsylvania, and had been for decades; William Penn himself had praised the many different kinds and sizes of fish to be found in Penn's Woods, and the settlers who came to his wilderness were pleased with what they found in the waterways. By the time Sam had set up shop in Easton, fishing had become such a widespread hobby that the city of Philadelphia had no less than four social clubs devoted to it. One of these was the Schuylkill Fishing Company, which was established in in 1732 and included President George Washington as one of its honorary members; the Company is still around today, and claims the title of the oldest continuously operating social club in the United States, if not the world. So fishing was regarded as not only fun and relaxing, but somewhat prestigious.

Sam greatly enjoyed trout fishing, and therefore knew firsthand the challenges which came with the sport. So he started making his own rods from a variety of woods - hickory is the only one I recognize, but he also used fantastical-sounding elements like greenheart, snakewood, lancewood, and lemonwood. Not altogether satisfied with any of them, he turned to using cane, experimenting with the processes of rending and laminating it in the style of English bowmakers. He continued his experiments, finally perfecting a six-strip cane rod around 1848. It's believed that he most likely used Calcutta cane, from India.

Sam was married twice and had two sons, Daniel and Solon; I found a reference to a daughter in one obscure source, but it gave her no name, and his record at FindAGrave.com doesn't indicate any other children. Daniel died as a young man and, as far as I can tell, never married. Solon served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and worked with his father making fishing rods. By 1859, they were making split-cane rods with laminated hardwood and bamboo grips. Sam and Solon formed a company in or around 1873, based on North Second Street, and advertised their services as being "Dealers in guns, pistols, powder. Bamboo and cane poles & joined poles made to order. Sewing machines, locks, etc. repaired and keys made to order." The company moved four years later to South Third Street, where the marker stands today; the building is, as of this writing, a Wells Fargo bank.

Sam passed away from pneumonia in May 1877, not long after the company's relocation to Third Street, and there was a fair bit of public mourning for the loss of the locksmith, violin maker, and fishing rod master. Solon continued to operate the business after his father's death, dying himself in 1925; he, his father, mother (or stepmother, it's not clear), and brother are all buried in the Historic Easton Cemetery.

Bamboo rods dropped out of popularity in the 1950s, because of President Truman placing an embargo on Chinese imports (making it almost impossible to get bamboo for a long time) and also because of the introduction of fiberglass rods. Easton's Sigal Museum has one of Solon's fishing rods in its collection, but as far as anyone can tell, none of Sam's rods survive to this day. But a good bamboo rod isn't hard to find, and I even found a number of tutorial videos on YouTube which instruct you in making your own. I think Sam would approve.

Sources and Further Reading:

Parkhill, S. M. "Easton developed the pole that has evolved into what is used today." The Allentown Morning Call, May 8, 1997.

Sajna, Mike. Days on the Water: The Angling Tradition in Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1999.

Author unspecified. Journal of the Franklin Institute, Vol. 41-42. Pergamon Press, 1846.

Samuel Phillippe at TheHistoricEastonCemetery.org

Samuel Phillippe at FindAGrave.com

Samuel Phillippe at the Historical Marker Database

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I would love to hear from you!