It frequently happens in my video games that while I'm on one quest, I stumble across multiple unrelated side quests (as they're called). MarkerQuest isn't all that different. It happens - quite often in fact - that while I'm out in the world simply doing whatever I'm doing, I stumble across those telltale markers which form the basis of this quest. However, it also happens, both in games and in real life, that one of the other characters will direct me to a side quest, and that's what happened in today's post.

I visit Peddler's Village in Bucks County with my mother a couple of times a year, usually in the company of friends. We were coming back from one such trip when she said, "You know, one of your signs is nearby. We should go get it."

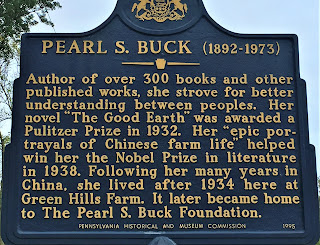

|

| The marker is located at the entrance to Green Hills Farm, at 520 Dublin Road, Perkasie |

The marker in question was that of Pearl S. Buck, the award-winning author of The Good Earth and many other writings. (No, she's not the reason Bucks County is called that, although I'll admit I did wonder.) She spent the last half of her life on a beautiful estate in the heart of the county, and her house is now both a museum and the home of her namesake organization. But she was born in West Virginia, so how, I wondered, did she come to live here? The official website of the Pearl S. Buck House has a PDF biography of her, which I will attempt to condense here along with information from a few other sources.

Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker was born in Hillsboro, West Virginia, on June 26, 1892. Her parents were Presbyterian missionaries, Absalom and Caroline Sydenstricker, and they had returned from China for a year's leave, during which time she was born; they had been serving there for twelve years and already had four children, three of whom had died in infancy. When Pearl was five months old, the family went back to China, where she grew up. She was raised in a bilingual environment, homeschooled by her mother with a Chinese scholar to teach her to read and write in that language. She was a voracious reader and a particular fan of Charles Dickens, whom she said influenced her own writing. Her mother insisted that she write something every week, and her first piece was published in the Shanghai Weekly's children's section when she was six years old.

|

| The house at Green Hills Farm, where Pearl S. Buck lived with her second husband and children, now a museum |

Pearl and John stayed in the United States for a few years when Carol was first placed at the school, during which time Pearl received an MA in English Literature from Cornell University. The couple adopted an infant girl, Janice, before they returned to China. During those final years in China, Pearl wrote her most famous book, The Good Earth, which received the Pulitzer Prize and was adapted into an Academy Award-winning film.

|

| The Rainbow Garden at the Pearl S. Buck House, with an inscription by Pearl's daughter Janice |

Along with her writing credits, which are about as long as I am tall, Pearl was involved in many humanitarian causes. She was a staunch supporter of the Civil Rights Movement and had a strong dislike of prejudice. She helped to found the Welcome House adoption program in 1949, the first adoption agency to specialize in the placement of biracial children, who to that point had always been considered "un-adoptable;" it continued until 2014, at which time it was phased out due to changes in international adoption regulations. Since 1964, the Pearl S. Buck Foundation (later changed to Pearl S. Buck International) has worked to make life better for children all over the world, as well as maintaining her landmark home.

|

| The grave of Pearl S. Buck |

Pearl died on March 6, 1973, just shy of turning 81. She's buried at the house, in the garden; her daughter Janice, who was active in her mother's foundation for many years, is buried nearby. She designed her own tombstone, which has no English epitaph, but rather is engraved with her birth name in Chinese characters. It's a lovely, quiet, peaceful place, and close to the grave the foundation planted a sugar maple, just like the one found at her birthplace in West Virginia.

I read a lot about Pearl S. Buck while preparing this, and it's been hard to distill all of it; there's much I've left unsaid. But she was a fascinating character, even aside from her writing skill. She was truly concerned for the well-being of people while at the same time not really all that fond of them. Most of all, I find it really interesting that she has this tremendous legacy of humanitarian work, and yet she insisted in 1969 that she was not a humanitarian at all. "When I become involved and find a situation that is not right, then I must try to do something to change it. But it is the artist's sense of order that leads me to undertake such a cause as displaced children, not any humanitarian feelings. I am a writer, and my work is to write books."

Sources and Further Reading:

Official website of the Pearl S. Buck House and International

Official website of the Pearl S. Buck Birthplace

Obituary of Pearl S. Buck in the New York Times

Obituary of Janice Comfort Walsh

Melvin, Sheila. "The Resurrection of Pearl Buck." Wilson Quarterly, Spring 2006.

Pearl S. Buck at the Historical Marker Database

Except where indicated, all writing and photography on this blog is the intellectual property of Laura Klotz. This blog is written with permission of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. I am not employed by the PHMC. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I would love to hear from you!